Location

Please select your investor type by clicking on a box:

We are unable to market if your country is not listed.

You may only access the public pages of our website.

We believe there are three main levers of change: policy change, through multilateral agreements by countries, legal challenge through litigation, and corporate and community action. All ultimately seeking to impose a price on pollution.

In our view, companies are increasingly vulnerable to policy and litigation risks, some are opting to set internal carbon prices (ICPs) to better account for this. An ICP is a self-imposed pricing mechanism that companies use to quantify the cost of their carbon emissions, incentivizing reduction strategies and aligning their operations with broader sustainability goals.

On the face of it ICPs have the potential to be an effective tool in increasing corporate resilience and reducing emissions. Yet the operation and consequences of ICPs are poorly understood.

As a firm, we have partnered with the University of Exeter to research this important lever of corporate policy. Find out more about our partnership here.

The ‘tragedy of the commons’ occurs when the self-interest of individual actors leads to the failure of the entire system. Unlike Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ when self-interest is the motivation behind trade, exchange, and economic prosperity, self-interest has led to higher emissions and deteriorating climate quality. Short-term economic prosperity has been achieved at the expense of long-term economic, social, and environmental prosperity.

Economists argue that this has occurred because environmental public goods are not priced effectively. There is no disincentive to pollute because the profits of activity are private, but the losses of from increased emissions are shared globally. From a purely financial sense, therefore, considering pollution could even put a firm at a financial competitive disadvantage in the short term against those that continue to emit. Especially given we are seeing the marginal cost of abatement increase.

This is an example of market failure as the full costs associated with economic activity are not captured. The answer for solving this problem may seem obvious: simply price the externality so that economic decisions will take into account their full environmental cost. However, what sounds simple in theory is hard to achieve in practice. With a single common atmosphere, a single common price would be most relevant. But that will require international agreement on carbon budgets, price setting mechanisms, and a reckoning, most likely, on the past benefit of historic unpriced emissions. This is difficult to achieve in practice.

Yet the world is constrained by a carbon budget above which the system is threatened and ultimately compromised. The socioeconomic cost of this budget being exceeded is immense1. So, although finding international agreement is hard in practice, the threat of failure has provided the motivation for countries to come together to try and resolve a path forward.

The annual COP climate change summits provided the forum for this with the 2015 Paris meeting seeing countries agree on their own contributions and targets to reducing future emissions. This was an important step in keeping the world’s emissions within the carbon budget, but nearly a decade later, progress has been varied and a Paris aligned world seems to be an unattainable dream. The global pandemic demanded an immediate governmental response that, in some cases, has absorbed the headroom to invest in energy transitions. It also highlighted societal inequalities, some of which have led to changes in governments, not all of which are as supportive of the aims of the Paris Agreement. This has led to warnings that climate change progress isn’t fast enough and that government commitments will not be strong enough to achieve what is needed to mitigate climate risks – a sobering reality. Relying on governments’ pledges, however, is not the only route for environmental progress. There are two others.

The first is legal. In common law legal systems, we are beginning to witness the application of the duty of care principle to environmental pollution. This is analogous to the arguments made against tobacco firms in the 1970s and 1980s which were sued for the harm their products did to customers. The harm was initially direct, but eventually it was successfully argued that it was also indirect through ‘passive smoking’. Tobacco firms were obliged to settle vast sums in damages. In effect, the litigation established a cost on the externalities of smoking, forcing the industry to confront its past business practices and leading to a period of much tighter regulation and higher prices.

Such arguments are now being used again, only instead of passive smoking, the law is looking to attribution science. Linking the effect of changing weather and rising sea levels with anthropogenic forcing, high emitting companies are increasingly finding themselves as the defendant.

These are difficult arguments to make and are hard to prove. Not all courts think the same on such matters either, but courts have a way of filling legislative voids with case law and, as such, often reflect the debates within and the opinions of society through the types of cases the public wishes to bring.

As the economic, social and environmental costs of climate change become ever more pressing, and the public more concerned, we should expect environmental litigation to increase. The primary targets are likely to be the legacy oil & gas, and broader energy companies, where the link to climate change is more apparent. It is less likely that legal action will be brought against firms in other industries where emissions are lower or where there isn’t a strong direct connection between the business model and carbon intensive activities.

This then leaves scope for the second possible alternative route for managing climate emissions: unilateral action from governments and communities. We are already seeing this in the way in which cities are choosing to implement road charging schemes, for example, or individual countries are considering carbon border adjustment taxes. For investors, all of the above approaches for addressing climate change, be that multilateral action agreed across countries, legal challenges, or local communities unilaterally pursuing change, expose corporations to increasing policy and litigation risk.

The above mechanisms may vary but in essence, the objective is the same: to ensure that carbon externalities are priced. Without change, the effect on corporations could be considerable. We are beginning to see some corporates respond proactively by anticipating this change and implementing their own Internal Carbon Price (ICP) when assessing business performance and new projects.

An Internal Carbon Price (IPC) is a mechanism through which companies can place a monetary value on their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as a way of prioritising low-carbon projects. It provides visibility on climate risk and costs allowing companies to develop strategies and steer business decisions in a way that protects the longevity of the business.

Practically ICP often takes several forms:

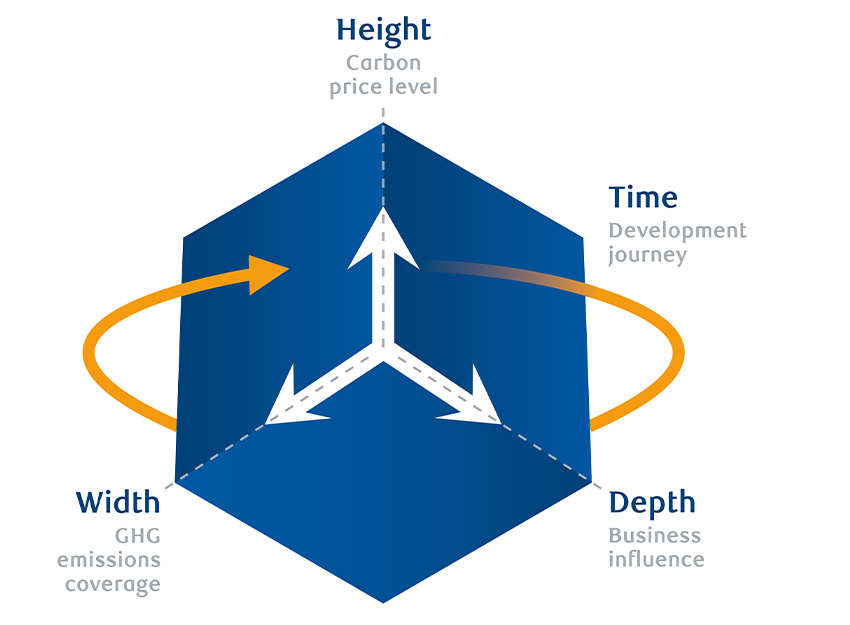

There are four main dimensions to any ICP; business influence, development journey, carbon price level, and GHG emission coverage.

The weight of each of these is heavily influenced by the macro impact of government policy, legal challenge, and community sentiment.

While ICPs are generally used to drive low-carbon investments, they also serve to drive energy efficiency gains, change internal behaviour, and stress test investments, as well as helping to navigate GHG regulations and stakeholder expectations.

Whilst the mechanisms of the internal carbon price are now well established, there is limited understanding of how this tool can be used most effectively.

Our sense is that the need for an effective climate transition is only becoming more pressing as time passes and the world’s carbon budget is fully utilised. The risks appear to be rising and for investors this is increasingly becoming something that is not just theoretical, but has the potential to influence the path of long-term profit expectations, such as considerations typically employed in discounted cash flows, which drive pricing in the market.

An Internal Carbon Price may thus be an important policy lever for firms to manage these risks and offer a signal to investors that their investments are more resilient to climate policy and litigation risks. This is why we have collaborated with the University of Exeter to research this area in more detail and why we now await the publication of that research with great interest.

Subscribe now to receive the latest investment and economic insights from our experts, sent straight to your inbox.

This document is a marketing communication and it may be produced and issued by the following entities: in the European Economic Area (EEA), by BlueBay Funds Management Company S.A. (BBFM S.A.), which is regulated by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF). In Germany, Italy, Spain and Netherlands the BBFM S.A is operating under a branch passport pursuant to the Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities Directive (2009/65/EC) and the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (2011/61/EU). In the United Kingdom (UK) by RBC Global Asset Management (UK) Limited (RBC GAM UK), which is authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), registered with the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and a member of the National Futures Association (NFA) as authorised by the US Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). In Switzerland, by BlueBay Asset Management AG where the Representative and Paying Agent is BNP Paribas Securities Services, Paris, succursale de Zurich, Selnaustrasse 16, 8002 Zurich, Switzerland. The place of performance is at the registered office of the Representative. The courts at the registered office of the Swiss representative or at the registered office or place of residence of the investor shall have jurisdiction pertaining to claims in connection with the offering and/or advertising of shares in Switzerland. The Prospectus, the Key Investor Information Documents (KIIDs), the Packaged Retail and Insurance-based Investment Products - Key Information Documents (PRIIPs KID), where applicable, the Articles of Incorporation and any other document required, such as the Annual and Semi-Annual Reports, may be obtained free of charge from the Representative in Switzerland. In Japan, by BlueBay Asset Management International Limited which is registered with the Kanto Local Finance Bureau of Ministry of Finance, Japan. In Asia, by RBC Global Asset Management (Asia) Limited, which is registered with the Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) in Hong Kong. In Australia, RBC GAM UK is exempt from the requirement to hold an Australian financial services license under the Corporations Act in respect of financial services as it is regulated by the FCA under the laws of the UK which differ from Australian laws. In Canada, by RBC Global Asset Management Inc. (including PH&N Institutional) which is regulated by each provincial and territorial securities commission with which it is registered. RBC GAM UK is not registered under securities laws and is relying on the international dealer exemption under applicable provincial securities legislation, which permits RBC GAM UK to carry out certain specified dealer activities for those Canadian residents that qualify as "a Canadian permitted client”, as such term is defined under applicable securities legislation. In the United States, by RBC Global Asset Management (U.S.) Inc. ("RBC GAM-US"), an SEC registered investment adviser. The entities noted above are collectively referred to as “RBC BlueBay” within this document. The registrations and memberships noted should not be interpreted as an endorsement or approval of RBC BlueBay by the respective licensing or registering authorities. Not all products, services or investments described herein are available in all jurisdictions and some are available on a limited basis only, due to local regulatory and legal requirements.

This document is intended only for “Professional Clients” and “Eligible Counterparties” (as defined by the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (“MiFID”) or the FCA); or in Switzerland for “Qualified Investors”, as defined in Article 10 of the Swiss Collective Investment Schemes Act and its implementing ordinance, or in the US by “Accredited Investors” (as defined in the Securities Act of 1933) or “Qualified Purchasers” (as defined in the Investment Company Act of 1940) as applicable and should not be relied upon by any other category of customer.

Unless otherwise stated, all data has been sourced by RBC BlueBay. To the best of RBC BlueBay’s knowledge and belief this document is true and accurate at the date hereof. RBC BlueBay makes no express or implied warranties or representations with respect to the information contained in this document and hereby expressly disclaim all warranties of accuracy, completeness or fitness for a particular purpose. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgment and are subject to change without notice. RBC BlueBay does not provide investment or other advice and nothing in this document constitutes any advice, nor should be interpreted as such. This document does not constitute an offer to sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase any security or investment product in any jurisdiction and is for information purposes only.

No part of this document may be reproduced, redistributed or passed on, directly or indirectly, to any other person or published, in whole or in part, for any purpose in any manner without the prior written permission of RBC BlueBay. Copyright 2025 © RBC BlueBay. RBC Global Asset Management (RBC GAM) is the asset management division of Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) which includes RBC Global Asset Management (U.S.) Inc. (RBC GAM-US), RBC Global Asset Management Inc., RBC Global Asset Management (UK) Limited and RBC Global Asset Management (Asia) Limited, which are separate, but affiliated corporate entities. ® / Registered trademark(s) of Royal Bank of Canada and BlueBay Asset Management (Services) Ltd. Used under licence. BlueBay Funds Management Company S.A., registered office 4, Boulevard Royal L-2449 Luxembourg, company registered in Luxembourg number B88445. RBC Global Asset Management (UK) Limited, registered office 100 Bishopsgate, London EC2N 4AA, registered in England and Wales number 03647343. All rights reserved.

Subscribe now to receive the latest investment and economic insights from our experts, sent straight to your inbox.